James F. O’Brien is a professor of computer science at UC Berkeley and has published numerous studies on destructive modeling, earning an Academy Award for his pioneering work in movies and games.

James F. O’Brien is a professor of computer science at UC Berkeley and has published numerous studies on destructive modeling, earning an Academy Award for his pioneering work in movies and games.

Communication is a fundamental skill for engineers. No one builds anything on their own. Whether participating in an open-source project or being employed to crank out code, you need to work with others. The value of effective communication skills cannot be overstated.

Even Linus Torvalds, a curmudgeon who will never lack work and whose word is law in the Linux community, has acknowledged the need to be more measured in his criticisms and more generous with empathy.

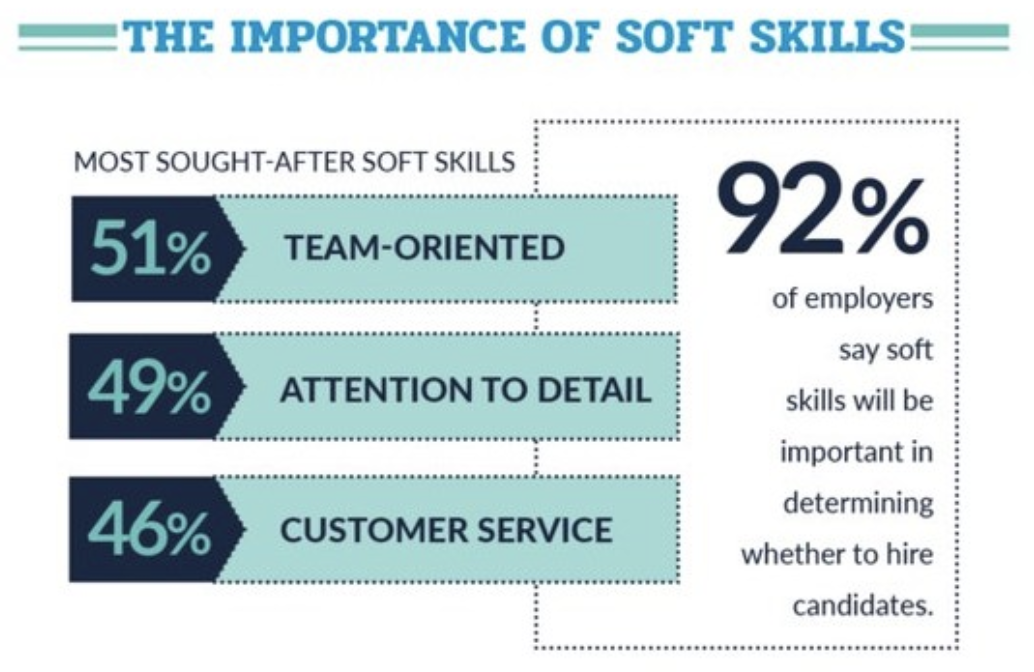

Soft skills, in the parlance of our times, are in vogue. Employers and potential collaborators will judge you based on your ability to lucidly communicate your thoughts in an agreeable and succinct fashion.

There are many great guides and books written about how to communicate effectively with other human beings. A lot centers around having empathy. Having an understanding of where someone is coming from, considering the information that they have that you don’t or vice-versa, and being respectful are basic tenets. I offer a few suggestions here:

Even when you are pretty sure of a fact you want to communicate to someone else, it is often better phrased as a question rather than a statement of fact.

“Why did you write it this way?” is infinitely preferable to “this code is wrong.”

If discussing a solution or implementation with someone, ask them what they think first, regardless if you already have a plan in your head. They may suggest what you are already thinking, may have thought about things you haven’t, and may bring up other good ideas. Especially for junior people; it helps them engage their critical thinking skills instead of learning to rely on you to provide the answer. It gives people more ownership and desire to defend their idea because it’s theirs.

This is one I am especially guilty of, and it has to do with knowing when to concede a technical argument. Very often there are no clear right answers for how to proceed with a feature or fix, and a healthy discussion of the tradeoffs can be illuminating and help arrive at a reasonable solution.

However since many tradeoff estimations involve a lot of guesswork and feelings and intuition, the “best” answer may never be agreed on. At some point you have to agree and move forward, and different people may have ideas of when that time has passed. I know I’ve driven at least one person crazy by continuing past the point they considered to be entering the domain of diminishing returns.

Often the proper solution isn’t clear. Agreeing on a proposal, prototyping, and gathering more data is more fruitful than making people exasperated or arguing for hours. Once you sit down to actually try it, it may quickly resolve the debate.

“Oho!” said the pot to the kettle; “You are dirty and ugly and black! Sure no one would think you were metal, Except when you’re given a crack.”

“Not so! not so!” kettle said to the pot; “‘Tis your own dirty image you see; For I am so clean – without blemish or blot – That your blackness is mirrored in me.”

If there’s one thing engineers love to do it’s complain about languages, libraries, tools, operating systems, service providers, interfaces, APIs, containerization systems, people on mailing lists, etc… When your tools don’t work right it can cause you hours of frustration and confusion, which nobody enjoys.

A moment’s contemplation will recollect the vast amount of sub-standard, buggy, hacked together balls of mud that the experienced engineer has thrown together in the past. If you write perfect defect-free code then you should continue with your expressions of distaste for the inferior engineers out there making fools of themselves. If on the other hand, you realize you have made plenty of blunders of your own, consider going easy on the target of your ire.

I’ve seen many online communities devolve into an ever-smaller group of grumpy guys, mostly chatting about how much everyone else is stupid and sucks. These communities sap your soul. Inject some positivity into your world when you can.

People aren’t mind readers and they generally are focused on their own work and problems. If you have information that may be useful to others, don’t wait for them to come to you and ask for it. If someone hasn’t asked you for an update or provided you with what you need, reach out rather than suffering in silence.

Over-communicating in a team is almost always better than under-communicating. By letting people know what you’re doing you can help others prioritize, not duplicate work, know whom to ask questions, inform you if they’re making changes that could affect your work, and reduce the need for people to make assumptions.

Assumptions are frequently foolish and rarely right. Often a brief message can save you time, making sure you don’t start off down a fruitless path. And by asking, you are communicating information about what you are working on and the fact that the knowledge you seek is not as widely shared or accessible as the owner of it may assume.

Nothing makes working with code others have written go smoothly like having comments liberally sprinkled throughout the source code. Whether it’s a new hire or yourself in two years when you’ve forgotten why you need to check that condition in that insane query, a brief summary of your logic and thinking at the time can help impart understanding and reduce the need for assumptions.

The goal is clarity and unambiguous communication of ideas. People aren’t mind readers and need a lot of information, some of which only you possess.

Thanks for reading!

Published using the Emacs-to-wordpress tool Org2Blog.

Talking with clients involves many variables like business, money, strategy, and of course the project itself. But no matter how good your code quality or analysis, the client will always remember how well you communicated.

Communication itself is an intricate jigsaw puzzle incorporating psychology and “soft skills” that can tease out what the client really wants – without the client knowing what they really want. Only through this type of “proactive communication” can you achieve the optimal results for you and your clients.

At JetBridge (and hopefully your work environment as well) we’re encouraged to speak up and challenge our clients if we disagree with the best manner of executing the project’s goal. This requires diplomacy and the courage to vocalize your opinions and ideas. Or as our CEO John often says, “Stand up for yourself. Speak up. Speak out.”

So I wanted to share what I now understand as some simple tricks and tips that help international software developers look and sound more professional.

Do: Send a letter where you ask which way/platform is most suitable for the client to use in order to connect with you. If you are suggesting any platform the client doesn’t have any experience with, make a small tutorial/call/text that explains how to use it and its benefits.

Don’t:

Tips:

Do: Make sure you talk the way your client understands. Talk with data, prepare analogies, and try to adapt what you are trying to say into something the client will understand.

Don’t:

Tips:

Do: Prepare a small list of talking points and issues before the meeting. If there will be several other attendees, research, and prepare who they are and what role they play in the client’s company.

Don’t:

Tips:

Do: Double-check what the client asked to do before you start because you may have different views of the subject. It helps to eliminate any misunderstandings and wasted time/money.

Don’t:

Tips:

Do: Make sure the client knows that the estimate is very rough and may change. If you’re not comfortable and hesitant to answer, tell that to the client and explain your reasoning. You also can ask for more time to answer. Don’t be afraid to “push back” on the client if it’s her or his fault that the project is being delayed!

Don’t:

Tips:

Do: Make sure the client knows the status of the projects at least once a week. Inform about extra added features, testing status, and any upcoming changes. The client should be comfortable with the amount of information they get.

Don’t:

Tips:

7. Delivering (parts/features): find the best way to show and explain the additional feature that you recently delivered.

Do: Send a small screen recording showing how the feature can be used and where to find it. Or make an appropriate explanation by text or using screenshots. The key point is to make a simple but useful guide for the client to see the feature and the progress. Eliminate any guessing part from the client-side.

Don’t:

Tips:

Do: Ask the client to review the added feature as soon as it’s delivered. Comment on how they can test it and where to find it. It should be easy for the client to see and understand what they should test. Demand that the client also help in the user testing!

Don’t:

Tips:

Perfecting both listening and speaking skills, fully understanding the intricacies of customer business, brand communication strategies, and its target audience will ultimately lead to success. I might say that every project, as well as a customer, is truly unique but the framework listed with 8 simple steps can perform miracles – not just for your client but for your career.