Kevin Lin Lee

Building a new food CPG company in public. Prev. Principal at Pear VC, Founder of Product Manager HQ, PM AltSchool & Kabam. Encouraging others to become creators.

Top 2 Lies Founders Tell VCs and more with Kevin Lin Lee

Interview w/ VC & Founder Kevin Lin Lee, Founder of ImmiEats.com – #1 episode of Federation.Dev Podcast.

- Do founders need to move to SF or not?

- Why big VCs started more frequently investing in food tech startups?

- What are the Top 2 lies that founders tell investors?

- What are the Top 2 lies that investors tell founders?

Transcription

John:

Welcome to JetBridge’s first podcasts. We we decided to do these JetBridge podcasts because we have so many super smart friends working on super interesting projects here in Silicon Valley. And we have so many great friends in Eastern Europe and teammates, and we really wanted to share the knowledge here over there. So I wanted to introduce Kevin Lin Lee. Kevin, can you give us a brief introduction of yourself?

Kevin:

Definitely. So from a professional standpoint, I started my career primarily as a product manager. The first company I worked at was a mobile gaming company called Kabam was very lucky to be there when they were scaling. It was a hyper growth scale from 300 around 1200 employees and under two years, and they later exited for north of a billion dollars. So really it was my first experience being at being at one of those Silicon Valley unicorns. Post that experience, I went to an education tech company called AltSchool. It was another high profile company that raised north of a hundred million dollars to try to reinvent education by building both software and hardware for education as well as running the physical schools themselves so that they could crappily test and iterate their products without going through the bureaucracy of the public school education system.

Kevin:

Unfortunately, that was a bit of an opposite experience in the sense of you know, the company tried to tackle too many problems at the same time. Ultimately they ended up restructuring as a nonprofit, but a very valuable learning experience there. And then after that, I ended up moving into the venture industry. The first venture firm I worked at was a firm called Founders Club. They were, it’s a little bit strange to hear, but they were actually a VC that went through Y Combinator and later raised money from VCs themselves. I think first round was their lead and it was a very good experience to kind of learn the ins and outs of the venture industry. They primarily did seed and series a, so companies with a lot more traction. And after that experience, I really was yearning to go even earlier stage and work with founders pretty much founders when they were in their garage.

Kevin:

And so I moved to a firm called Pear Ventures. It used to be called Page Monmar, and it’s a legendary founder named Paige Mon who started in Silicon Valley as a rug salesman believer or not. So he escaped Iran, came your homeless, sold rugs for north of 10 years. And basically became the first angel investor in companies like Dropbox, LendingClub and at Pear it was a primarily a pre-seed and seed stage firms. So investing at the earliest stages of a company lifecycle and they had around $125 million under management when I was there. And last month they recently raised their third fund, which was $160 million.

John:

You mentioned FundersClub which I think at one point resembled angel list a little bit, correct. It was more like a more exclusive, more professional angel list. And as we were saying before this podcast how we met was at a FundersClub’s dinner, because one of your colleagues, Pedro Sorrentino, right saw me wearing a suit at 2:00 AM at the El Ferlito mexican restaurant down here on 24th street and said, bro, what the fuck are you doing wearing a suit? Which begs the question. And by the way, Pedro Sorrentino now has his own fund One VC, which him and his partners are just amazing. I think it’s going to be an absolute stellar fund. But it begs the question. You know, I met Pedro at two in the morning at a Mexican restaurant in San Francisco, which is then later how we met a lot of European founders are asking themselves, do I need to be in San Francisco? Do I need to live in Silicon Valley? What do you think?

Kevin:

That is a great question. There is a fascinating interview between Marc Andreessen and this guy named Brian Koppelman. I believe he’s the creator of a few famous shows. One of them is called Billions out here. But the two of them talk about Hollywood and they talk about the importance of putting yourself in the scene. And what that means is, you know, there are a lot of writers. There’s a lot of actors, actresses, everyone in LA is trying to make it big and become the next famous actor. But a lot of them complain that they say, Hey, look, I think I’m an excellent actor, but why am I not getting these auditions? Why am I not getting the chance to showcase my scripts and Marc Andreessen and Brian Koppelman talk about this importance of being in the right environment, being in that scene, because if you’re not in that scene, you won’t create enough serendipitous moments.

Kevin:

Like John just mentioned where at 2:00 AM, you’re going to be meeting the next director who takes a chance on you. And I think still can Silicon Valley, especially in San Francisco is very much the same way. A lot of people have many complaints about this city. There’s obviously a lot of issues with homelessness. There’s a lot of kind of income inequality here, but the truth of the matter is you want to come here because you want to be part of that scene aware again at 2:00 AM, you can come across the next person who might be your co founder, who might be your lead engineer, who might be that investor who takes your company to great Heights. And so do everything you can to be surrounded by the smartest people in the world. And yeah. Put yourself in that scene,

John:

Be prepared to pay $3,500 a month.

Kevin:

Yes, that’s it.

John:

Why become a founder again? Well maybe I should back up. You have recently made the jump back to being a founder. Can you talk a little bit more about your new startup? Yeah. So

Kevin:

Back when I was at Pear, I actually was leading their food and beverage investing. And the funny story is that I’m actually the grandson of farmers in Taiwan. My, my grandparents have been, they’ve grown this fruit called a rose apple, or a wax ppple for decades now. And I actually, when I grew up as a child, I spent most of my summers and winters, literally in the fields with them harvesting, packing, you know, stemming the fruit. So I would like to say that food and beverage is really is in my blood. And it’s ironic because my family, my parents immigrated to the US literally with nothing in their pockets and they wanted to get me away from that industry. And now I’m coming right back in. So the company that, you know, my cofounder and I started it’s called IMMI. (www.immieats.com)

Kevin:

And what we’re trying to do is we’re trying to build the leading better for you Asian American food brand here in the U S and there’s a couple of reasons behind this one is a very strong personal mission. My grandparents, despite being in the food industry did not have the same level of food education that I did here in the US so my grandmother is pre-diabetic. She recently had a stroke from high blood pressure that left her half paralyzed, and both of my parents have taken medication for high blood pressure for over a decade. Same thing with my cofounders family. And what we realized here in the States was that this isn’t an issue that’s prevalent just amongst Asian-Americans, but across most Americans in the US diabetes high blood pressure is a major chronic health issue. And we grew up again in Asian food families.

Kevin:

It’s an industry that we understand my cofounders father actually runs an Asian supermarket down in LA. His grandmother used to run. One of the most famous noodle stands in Thailand. And so we both recognize that we have a lot of family history, a lot of industry domain expertise here. And what we saw was a number of changing macro shifts in the US so my co founder was actually recently a lead product manager over at Facebook, and he was starting to see some really interesting ad data around spend for food and beverage as a category. What I saw at Pair ventures was obviously the, there in America, people care a lot more about eating healthier and better for you products. It is just a shift where what you’ll notice here in the US is that once you start eating better, you don’t ever go back.

Kevin:

It’s, you know, I don’t think you can ever eat healthier and then tell yourself, nope, I actually want to die earlier. And so what’s happened is across the US you go to these natural grocery or these specialty grocery markets, or you go to whole foods, and every single aisle has completely changed. Every single food product is completely different. And what I saw when I was at Pear was that not only was each category changing, for example, yogurt became Chobani, which is Greek yogurt, less sugar, but I was seeing entire cuisines being reinvented. So Mexican food, there’s a company called CA Day Foods that took all of staple Mexican products, like tortilla, tortilla chips, and they’ve reinvented them with better for you ingredients. And they recently raised $90 million from Stripe’s group to take over that entire sector, all of Mexican food and what my cofounder and I saw was that no one was doing this with Asian food.

Kevin:

So we started Emmy with this thesis in mind to, to become the leading better for you Asian American food brand. And the first product that we built was a low carb, high protein, instant ramen, because instant ramen is a $40 billion category that no one pays attention to is likely the product. You first learn how to make as a child. When your parents were out of town, a is a product you perhaps ate in college as a porch college students, but you never really paid much attention to it as an adult, unless you were drunk at 2:00 AM, because it’s just terrible for you. It’s high in carbs. It has no nutrition. It’s high in sodium. It’s typically deep fried. And so we saw this opportunity where Americans were clearly still consuming it. 4 billion servings are consumed every year. And it’s a growing category, but it’s much more popular in Asian countries as a stable food and not necessarily here in the US because Americans care about their health. So we worked with a food science PhD and a chef over a year to really create this again, this low carb, high protein, higher fiber instant ramen that has the same familiar taste and texture. But it’s just 10 times better.

John:

I know decent foods who makes, you know, the 800 Pounds. They make a cup of noodles, which I grew up on. I know they’re working on a dehydrated beef stick that with hot water will actually tastes like beef. How are you guys getting, or how do you guys plan to get more protein in a healthy way into packaged noodles?

Kevin:

Yeah, so we actually use a combination of specialized plant proteins. We actually went through over 50 different proteins to identify the specific ones we want to use in our current formulation. But our current formulation has approximately 37 to 40 grams of plant based protein has around eight to 10 grams of net carbs. That means it’s very, very low in carbs. You’ll actually stay very lean and fit if you continue eating our product. And as around six to eight grams of fiber, which is really good for your digestive health. So again, we, we chose very specific plant proteins. We are primarily going to be a vegan product actually as well. So even though our flavors, our beef or Japanese pork tonkatsu, we use a specific yeast extracts to make sure that they’re actually vegan friendly.

John:

Got it. I know everyone probably is going to ask you or has asked you, can you make vegan dry packaged noodles tastes good?

Kevin:

Yeah, it is a, it is a great question. And I think my cofounder, I have very high standards because we grew up eating the stuff in Asian households. So we try to ensure that our own demographic would enjoy eating this product. I think the truth of the matter is that Asian-Americans are going to be the most critical of an Asian product. Just like how, if I gave a chickpea or lentil based pasta, like a bonzer to an Italian, they probably scoff in my face. They’d say, what the hell is this? This is, this is not the product I grew up eating. So we recognize that our early adopters may in fact not be our own race. That’s, that’s just the truth about any kind of cuisine that’s specific to an ethnicity. But our goal obviously is to get our own race, to love our product. As, as we start to become a little bit more mainstream. Now, again, that being said, we, we have gone fellow Asian-Americans to really enjoy eating this product. So that is definitely the, the goal here, right?

John:

My brother just became an executive at a Chinese CPG consumer packaged goods company. And I was shocked when he told me their fastest growing segment of customers, or is actually the Latino market. The Latino market apparently is exploding as a consumer of packaged Asian foods. Right. one of the things I noticed though, is when I go to 99 Ranch, cause I’m Korean American and I’m a bad Korean.

John:

My wife’s Korean is better than mine and my wife is Ukrainian. When I go to 99 Ranch, where I see a lot of Chinese products, the packaging doesn’t make sense to me. So I have to go by the picture if there is a picture, right. When I go into the Korean market you’ll see one or two Japanese brands that bleed over, but usually they’re Korean packaged goods in Korean. Right. and again, you kind of have to go by the picture within me. Do you guys have or have you guys discussed how you’re going to brand and communicate the ingredients and the benefits in a way that’s not so confusing? Yeah.

Kevin:

Yeah. That was actually a big motivation behind this brand to begin with. When we, when we thought about our own experiences and talking to some of our non-Asian friends, you know, if you’ve ever walked into, I think you mentioned a 99 Ranch or any Asian supermarket, it is almost like a carnival in there. There are hundreds of different brands, all bright colors, confusing. It’s confusing as hell. It is. It’s scary. It’s really scary. Right. And it’s really hard to figure out which brand to trust what the ingredients are. Literally some of these, the packaging will say may cause cancer. It’s just not the thing that you want to see on food. And so my cofounder and I, what we did was we actually approached one of the best branding and design agencies for food and beverage. It’s, it’s probably a little bit uncommon because I think in traditional tech, you typically hire in-house designers.

Kevin:

You want to build that talent in house for a food and beverage brand in the early days. A lot of us will end up outsourcing branding to experts and the one we chose Gander, they’ve actually designed some of the best performing food brands more recently. So a lot of the better for your brands. One of them is called Bonzo is a, the first chickpea based pasta, one of time’s best inventions. They are the fastest growing pasta brand in the US very simple, clean packaging. It is a bright orange slash red box explicitly says, made from chickpeas and lists two distinct nutritional call-outs, which is their high protein and their high fiber. So if you look at this box in the pasta aisle, it stands out because every other box is this dark blue, really boring kind of shade. And there’s just, it’s really bright.

Kevin:

It’s very clean. And it just lists a few core ingredients. I think they have four ingredients. Gander has also done another brand called Magic Spoon which is the fastest growing cereal brand in the US they are a keto friendly, low carb, high protein, low sugar cereal. They recently raised a 5 to 6 million dollars series a around from Lightspeed after only being in the market for three months. So they’ve grown so quickly in three months, they raised that series a round. And again, Gander did their brand as well because it’s a very clean box. Has you know, I think because cereal has often been viewed as a children’s brand they still have this iconic kind of like hero on the front of it, but it explicitly lays out, you know, the sugar content, which is extremely low, the high protein, the low net carbs.

Kevin:

And we take a very similar approach. So we’ve been working with this branding agency for two months now. We’re still on, I think, revision 2.5, something like that. But we’re going for a very clean label look. I think ultimately for instant ramen, you still want to display a bowl of prepared ramen because instant ramen at a package is not that appealing looking. And people ultimately are very aspirational. They want to know what the finished product might look like, where it includes maybe like a cut, you know, egg soft, boiled egg Shasha pork stallions. So there still needs to be that imagery, but the nutrition label should be clean label. You should have call outs of the nutrition facts. So for us, it’s very low in net carbs, high in protein. So those are likely the two things we want to call out.

John:

Right. I noticed with a lot of consumer packaged, or at least the, the ramen or the noodles, you know, the picture always looks like you ordered something at Momofuku is in New York city. It’s perfect. But when you actually make it at home, you know, I did a Google search before you got here. And I just Googled dry packaged ramen. And in the SERPs, the search engine results page there’s a question section that Google now includes in a lot of search results that says people often ask. And the top question people ask is, is ramen noodles healthy? And then when you click the expand, it basically says like, no stupid!

John:

How do you and your partners think about packaging, the ramen to show people that, Hey, this is different. It’s actually healthy.

Kevin:

That is a great question. And it is a question that we actually got from a number of our the VCs who invested in our round. A lot of them said, well, this industry has so much negative stigma around it. How are you going to break that kind of anchored bias that consumers already have? The example we typically bring up again, are a lot of these better for you brands that I just mentioned. So for example pasta, it’s not necessarily seen as an unhealthy, but it’s historically just seen as a traditional, you know, you just use white flour, it’s high in carbs. It makes you crash. There’s nothing, there’s not any necessarily anything nutritious about it apart from just kind of being a filler food. And Bonzo was able to change that by talking permanently about chickpeas and how chickpeas were really high in protein, high in fiber Magic Spoon, same thing.

Kevin:

If you think about cereal for the past decade general mills, Kellogg’s, they’ve effectively just been pushing sugar bombs to children. If you look at most cereal packages, some of them can be as high as like 40% sugar content. It’s kind of ridiculous that we’ve been giving our kids this for so long and magic spoon came along and said, well, look, you know, how come you grew up, but your cereal didn’t. And that was really this marketing positioning that they pushed as DTC a direct to consumer brand going e-commerce first, they were able to control their messaging, their positioning, their PR and really tell people, look, we have reinvented cereal. We are a low sugar, high protein, low carb cereal. That’s actually a good for you. And I think the difference these days with most food and beverage brands is that a lot of the best performing brands no longer take the standard approach of going retail first of going grocery, I’m doing trade shows of doing demos and setting up these little booths in the store. There’s just not as much of an opportunity to tell your story that way, because consumers are walking down the aisles, you have two to three seconds to get their attention, and they have that same stigma of you have that category versus these days, the best performing consumer brands, because they’re selling direct to consumer because they own their marketing channels. They own the relationship with that end consumer. They’re telling their story online. They can really help educate the consumers directly, and they don’t have to rely on a retailer or grocer to do that for them.

John:

Does your ramen need to be refrigerated?

Kevin:

No. So what’s interesting about our ramen noodle is when you think of an instant ramen, you think of the dehydrated noodle bricks that are typically deep fried. We’re actually taking a slightly different approach. We’re using a fresh noodle in a special type of packaging. So it’s probably too many too much detail right now, but we can, technology has really changed where you can effectively acidify a noodle and put it in a special type of vacuum seal packaging that makes it shelf stable. So it doesn’t need to be refrigerated or frozen. It’s going to have a shelf life of eight to 10 months.

John:

So you can ship it direct to consumer as well for pretty cheap.

Kevin:

Exactly. And I think that’s really the interesting thing here where all the historical giants, the Nissens of the world they’ve really lived within retail. And it’s funny because I think I recently went through the 10Q of Nissen and one of their slides quite literally says, we think we can appeal to the younger demographic through e-commerce. It’s like one of those complete bullshit slides you see on an, like a strategy deck. It just goes to show that a lot of them don’t really understand e-commerce. And so we believe that with our shelf stable product, that’s really relatively light to ship. We can build a fast growing direct to consumer brand in this space.

John:

You know, Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator coined this term ramen profitable. Yes. Because ramen is so fucking cheap. So how can you guys price your product to make it a good product for your company in terms of margins, but also not have people wince at the price? Can you guys, is that possible?

Kevin:

Yeah, that is again, also a great question. So all better for your brands because they use expensive ingredients. When they first launched to market, they always launched with a premium price. Oftentimes we see multiples of anywhere from three to 10X, what standard brands used to have. And this is obviously a very tough pill for most mainstream consumers to swallow. And this is exactly why you don’t want to launch within the Walmarts or the Targets of the world, because that consumer demographic is going to recoil at the thought of paying $4 to $5 for an instant ramen packet. And realistically, we are going to have to launch at the four to $5 price range because our, our costs are significantly higher than what a Nissen or like a cup noodle brand is using. They’re using traditional white wheat flour, which is the cheapest possible product out there that has no nutrition.

Kevin:

And then they deep fry in canola oil. We’re using specialized plant proteins, very expensive, very good for you, but we’re launching at a premium price to make sure that we have enough of a sustainable margin to grow quickly and have ideally you know, we can break even on the first purchase. How we, so what I usually tell people, again, a lot of our investors ask the same question. What we did in the early days was we actually built a few landing and we did a bunch of demand testing. So we integrated some checkout forms and we actually collected preorders from consumers at the price at the desired price point that we wanted. So we ran a number of paid ads, ensured that we had a very positive return on ad spend to know, Hey, look at the worst case scenario.

Kevin:

If we had to scale through paid social, could we be profitable? Is there enough demand for this price point for this product? And when we answered that question, we said, yes, there is. Then we actually went and built the product. So we did de-risk and mitigate this. Two is that we looked at certain comps in the market. So one of our investors, actually a group of our investors are from a company called Kettle & Fire. They are the fastest growing bone broth brand in the US they grew from zero to north of I can’t say the exact numbers, but north of $30 million. They’re, they’re higher than that in, in about three years which is very, very fast for a food brand. And when they launched to market their bone broth was something like $10.99 per carton.

Kevin:

And if you look at traditional broth in the supermarket, it’s like $2.99. So you’re talking a huge, huge differential here, but they sold out like the first 30,000 cases within less than six months, because they knew that if they attracted a specific type of demographic, which is a premium obviously a higher income customer, those customers tend to be less fickle, less picky. They complain less. It’s kind of like how, as an enterprise software company, you know, you’d rather sell to just one, $1 million customer than, you know, a thousand like smaller customers who are all going to complain about certain things. They focus their efforts on a higher income bracket customer, and then over time as they scaled, they slowly brought down their price range and now they are a much cheaper product. And that’s how we’re planning to do the same thing.

John:

Do you know of these the folks at Perky Jerky? I was at a summit series a few years ago and I met a couple of guys and they wanted to reinvent jerky and you know, they, they said, look, beef jerky sucks, it’s right. You buy it at $7-$11 and it’s really hard to chew. It’s really bad for you. And it has a limited demographic. Like when’s the last time you saw a young woman snap into a slim jym.

Kevin:

Right, right.

John:

And they have a, it’s pretty expensive. It’s sold at whole foods. I think it’s like $6.99 for a small amount of turkey jerky, but it’s amazing. My wife loves it, everyone I’ve given it to loves it. And I think perky jerky discovered maybe by design that look a whole bunch of people that wouldn’t eat beef jerky will eat a healthy turkey jerky that tastes good. Do you and your partners imagine that Emmy, that you guys are going to be addressing an audience or a demographic that typically doesn’t even know what a Ranch 99, like they’re listening to this. They’re like, what’s ranch 99. That sounds good. I want to go with it. Or normally wouldn’t consider themselves a consumer of dry package.

Kevin:

Yeah. So, you know, funnily enough, so we actually have a beta community that we run on Facebook. It’s around a thousand people right now. And we’ve noticed from looking at the profiles that something like 95% of the profiles are actually non-Asian. And this goes back to that, that, and what’s the name of the Facebook page? It’s, it’s actually a private beta group. It’s called, it’s an Immi’s private beta group. But if you subscribe to our email list at ImmiEats.com there’s a call to action to join our Facebook group.

Kevin:

And so we know that there’s probably a few segments we’re going to address. One is, you know, people who ate instant ramen at some point in their life, but then churned, where they no longer eat it as an adult. And that’s very much like how Magic Spoon targeted cereal towards adults who ate it as a child and never again. And then there’s a segment of people who Americans, who never have had an instant ramen period, which probably is very unlikely. It’s a very popular food, but and then we’ll try to figure out how to convert them into eating our product. Now, what I would recommend, I think there’s hopefully a lot of startup founders listening to this podcast what you want to do in the early days. And this is pretty obvious for, for people in tech, for food and beverage.

Kevin:

We did a lot of not just demand testing, but demographics testing when we started out. So some food brands they launched, they have no idea who their target customer is. Because my cofounder and I came from product management backgrounds. We ran a series of structured demographic tests on Facebook, through Facebook ads, where we ran ads with the same kind of copy ad creative. But we, we altered all the different demographics and we really want to see what was the cheapest cost per lead for a certain demographic. And that would tell us, Hey, look, it looks like, and what we learned with for example, was that our primary audience we thought was actually going to be men because of our high protein count. Actually 80% of our demographic is actually females. It’s females between the ages of 25 to 44 who are interested in health and wellness.

Kevin:

And then within health and wellness, we subs we basically did another round of demographics testing to subsect that out even further. So not only do we know that there are females interested in health and wellness, we know they are females interested in health and wellness. They are also interested in yoga, cycle, running, mindfulness and meditation. I’m just listing a few examples here, but you can get extremely targeted these days with your Facebook ads testing and therefore when launch, you know, exactly how to write all of your marketing copy, you know, what kind of images to put like from a lifestyle perspective you know, which channels you want to be focusing on because, you know, that’s where your customers live. So we funneled a lot of these people into this beta community where we’re nurturing them over time. And when we launch we know, Oh, by the way, also a lot of this went into the design of the product. So we were able to funnel all of this research to our branding design agency to let them know here’s our target demographic. We probably want to design around that.

John:

You mentioned, and I’m a big fan of this, that before you guys did a lot of other things, you first spent some money on a landing page and some ads to measure, maybe not the CAC, but just to measure some of the top of the funnel metrics. Correct. And I, I see a lot of first time founders, not just in Europe, but you do see it a lot in Europe where they spend a year or two years, right. Or like that old professor in Moscow who has been like working on this for 20 years. And he’s like, just about to release it when it’s perfect. As a general rule of thumb, do you recommend that young founders, first time founders maybe spend two, three, $5,000 a month or $5,000 in total for a month period or so, just to see what the top of the funnel metrics look like?

Kevin:

Yes. I tell this to almost everyone. And I think the issue is that we, we see this a lot in Silicon Valley where people, you know, they think like, Hey, you build a great product. People will come regardless. Marketing is, is frankly, half the battle. And if you don’t do demand testing early on, you run that risk. Like John just said of building, you know, in a, in a silo for two years, launching and realizing no one cares about your product or maybe the world has moved on. I think there are a few exceptions. Nowadays, you know, there are companies like Superhuman, a few others that have been really product focused, built for two years, launch with an excellent product. But even for them, you’ll notice they’ve been doing user research the entire time. And so for any founder, before you start building anything, it’s very easy to build landing pages.

Kevin:

You can use tools like Unbounce to build a landing page. We used another widget called Celery. It lets you embed a widget to collect preorders, and then you can spend, you don’t even need to spend $5,000. You could probably spend like $500 a runner for your Facebook ads test what the conversion looks like. You know, you can see what your AOV (average order value) is. So for us, for example, we want to make sure our average order value was high enough where based on our paid customer acquisition costs, our average order value was high enough where we could break even for example, on a first purchase or a second purchase. And again, there’s probably a lot of software founders out there who are listening this, I’m actually not sure of the breakdown, but even as a SaaS company, maybe you don’t have a product.

Kevin:

Well, at least you can get people to subscribe to your email list or get them to sign up for a consultation or a call, or you as a founder can then email them, reach out and do user research. And this is something that Superhuman did really effectively in the early days. I think they, they would let people sign up. They would reach out and they would schedule these calls to understand their email habits. So, you know, are they power users? What were the issues? They had an email and this is how they learned that speed was critical. So again, don’t do not build in a silo, try to do as much demand testing as you can or at least use our research in any way or matter before you spend two weeks, two years in a silo building your product.

John:

I think you’re right. Superhuman is one of those rare exceptions, by the way, the founder of superhuman has a great podcast that he did for Jason Calacanis on twist this week in startups, which I recommend to everyone. It’s great nd one of the things that I was really shocked because he’s, you know, he’s so smart, but he’s, he’s very like to the point. He’s very honest. You know, he said we raised our net promoter score with our power users by narrowing the definition of who’s a power user.

John:

Oh, that was great. But they’re so hyper focused on the user experience, but I think you’re right. They, they kind of are there are rare exceptions and the way they thought about the velvet rope marketing, where like you can’t sign up to have a friend invite you, I just thought was brilliant earlier you mentioned Lightspeed. And for those that don’t know Lightspeed as a tier one VC, they have offices in Tel Aviv and here in Silicon Valley as well. Renowned VC, great track record. You mentioned that they invested in a consumer packaged goods food company. 10 years ago I don’t think we saw tier one VCs or maybe even VCs investing in beds mattresses, right. Stationary bikes, reinventing cereal package, ramen, the fuck is going on. I thought we wanted to see high margins like licensing margins. Is there too much money floating around or our VCs recognizing that there are things beyond just software?

Kevin:

Yeah, that is that is definitely a very pointed point. So I, there are definitely examples of companies that frankly have raised too much money. And some of these unfortunately are consumer brands they’re direct to consumer brands, companies that with the margin profile that they have and the rising acquisition costs on most paid social channels really shipped where it should not have been raising that much money to begin with. On the flip side to that, I think is perhaps just a, especially in American culture where direct to consumers, just as a concept is I would say relatively new where you look at some of the incumbents. And I’m going to specify specifically in food and beverage, as an example, the incumbents in this industry, the Proctor & Gamble’s of the world, the Kelloggs, General Mills these are decade old companies.

Kevin:

They’re all, most of them are all public companies and the incentive structures are all wrong because you look at kind of the trends of how consumer behavior has changed, what people care about from a, from an eating habits perspective. And a lot of these old companies are still creating the same shitty, terrible, unhealthy products. Now, the issue is most of these CEOs, they recognize this too. They’re smart people. They’re not dumb. But the issue is that as a CEO, if you try to change your product portfolio ones that has been making you billions for the past decade, and you try to create better for your products. Problem is as an incumbent, you’re still servicing most of mainstream America and most of mainstream America, there’s still a big population that isn’t eating better for you.

Kevin:

And if they changed their formulas, their sales are going to drop now as a public company CEO, if in the next quarter, your sales drop, what’s going to happen. Your board is going to fire you. So as a public company, CEO, it’s a completely misaligned incentives where you have no incentive to innovate unless you straight up acquire a company. And what this has caused is it’s effectively chaos, where a lot of these incumbents they’ve basically turned over CEO’s like 12 times, you know, in the past few years they can’t change anything at this point. There, again, the incentives are broken. So you see a lot of these upstart brands brands like ourselves, or like the Magic Spoon and bonds of the world who see an opportunity to capitalize on changing consumer habits, trends, and, and build these large brands to basically take away pieces of companies like Proctor and gamble. And if you look at a company like Proctor & Gamble, each particular like each product within the portfolio can alone be a billion dollar brand. And so I think a lot of VCs are recognizing that this is happening, not just within food and beverage, but you look at your average home. You look at a couch these days that we have direct to consumer brands selling couches only, or mattress companies like Casper, 8sleep, Lisa and these are all billion dollar, multi billion dollar companies just waiting to be built.

John:

So VCs no longer focus as much on wanting to see 70% gross margins. They just want to see growth.

Kevin:

I don’t think that’s necessarily true. I think they still care a lot about gross margins. And I think recently, especially across the Twitter sphere, there was a huge debate you know, around the importance of gross margins, especially now that I don’t know, SoftBank, you know, has kind of come and plowed their money into all these companies. And they haven’t really seen the return that they’d like. WeWork with the biggest scandal recently around that. I think though with direct to consumer brands, you actually can, you, you’ll probably never get to the software gross margin, but there are a lot of brands. For example, there are a lot of food and beverage founders that I know some of them are investors in our company. That’s how I know some of the insight information they have reached that glorious 70 to 80% gross margin, which is, you know, you can, it seems unheard of, and this is specifically direct to consumer.

Kevin:

And again, this is because you’re cutting out so much of the middlemen in this industry. A lot of the retailers wholesalers that historically would want to take cuts. But you know, the beauty of internet, again with eCommerce is you’re selling direct to consumer. You own the entire life cycle, the transaction life cycle. You know, you’re running everything from the paid ads all the way down to acquiring that that consumer. And so you can get the gross margins that traditional software has seen. Now, that’s a little bit different when you enter a retail and you’re selling within brick and mortar, or you’re selling within grocery there. You’re not going to see the same gross margin, but where, what you see there is you see scale from a volume perspective. And these brick and mortar locations are channels that traditional software companies don’t get access to because they’re selling software. But for food and beverage, for example, we have all these different retail outlets. And I think people forget that something like 99 point something percent of all shopping is typically still done in brick and mortar is at least in food and beverage. So that’s still a huge market there, right?

John:

Let me close with a couple of founder hack questions. You’ve been on both sides of the fence as an investor and as a founder, multiple times. As an investor, what are the top two or three lies that founders tell you, even if it’s lies that founders believe themselves?

Kevin:

Interesting. So I think one lie, one lie that I see a lot at the early stages is a lot of founders claim that they know their LTV to CAC ratio. You’ll see, often in a lot of pitch decks, a lot of these founders will say, we know our LTV to CAC is 4.5X. And I think at the earliest stages is almost impossible to estimate this ratio. You know, for one, a lot of companies, whether you’re a SaaS company, whether you’re a consumer brand, you just haven’t seen enough cycles, whether that’s like turn cycles or, you know, like subscription cycles to know what your true LTV is. Two is you probably haven’t built like a full multitouch attribution model to know your, your CAC down to the details. So it’s just really hard to estimate. So I think it’s good to have an estimation.

Kevin:

I just think a lot of founders are a little bit too confident when they, when they throw out that number and they think that that’s their ratio, that’s going to stay as they scale past, you know, their series B. The second I see, and this is very prominent and it’s bite, it’s not really at the fault of the founder. It’s just kind of this power dynamic between VCs and founders is that founders lie in that they have to always tell a VC that they’re crushing it or that they’re killing it, or they’re doing incredibly well. It doesn’t matter what terminology you want to use. Right, and again, it’s by no fault of the founder, because as a founder, it doesn’t matter if you’re doing a friendly meeting with a VC. It doesn’t matter if it’s a coffee meeting. Doesn’t matter if you grew up with this VC, every VC meeting is a pitch meeting.

Kevin:

Don’t let anyone else tell you otherwise, because if let’s say I’m just meeting with a founder friend, if they told me like, Oh man, look, I lost my CTO. This quarter sales haven’t been doing that. Well, I think we’re going to pick it up in my head, have already created this anchor bias where I think, Ooh, that doesn’t sound that great. So the next time I meet with him or her, when they’re thinking about fundraising, I already have this bias where I’m like, I know a little bit too much here. And I’m not sure that this would be a good investment and a lot of VCs will then tell their VC friends because words travel super fast. And founders call this poisoning the well, you don’t want to poison the well and let VCs know you’re not doing well. Otherwise it’s going to spread quickly and you’re not going to be able to fundraise. So as a result of that, your incentive as a founder is to always tell a VC I’m crushing it. I’m doing incredibly well. And this is pretty much, this is very paralyzing. That’s why you see a lot of founders with mental health problems because they have no choice, but to say stuff like this. And I think that’s, that’s just, unfortunately, one of the lies that, that happens a lot here.

John:

Yeah. I think especially with first time founders, the pressure to fake it till you make it is immense. It’s why I was on Ambien for years. It’s hard to sleep at night as a first time founder. You mentioned CAC and LTV for those that don’t know CAC is your customer acquisition costs. Like how much money do you have to spend on Facebook to get that customer and LTV longterm value is how much does that customer pay you over their lifetime? And I think you’re absolutely right. It’s, it’s hard to know because you don’t know what your churn is yet over the next year or two years. I find another lie is a strong word, but I find another thing that founders, especially first time founders talk about a lot, maybe inaccurately is the TAM or total addressable market. Like how many customers for you are out there. And I think it’s misleading, like in the case of Perky Jerky, like look traditionally women in America don’t buy beef jerky, but they’re eating perky jerky. Right. So how do you measure what that TAM is? My first startup five, nine, we were in the call center software business.

John:

I remember, you know, when you’re a first time founder and you’re trying to put together this TAM slide for investors, you do a Google search, like how big is my industry? and then there’s always some report from Forester or from Ovum that says, well, for $2,295, I’ll tell you!

John:

But I remember paying for one of these reports, I was so desperate to raise money and it said the call center software market, just the pure play software part in north America. And this was back in 2003 or four was $220 million a year. Now that company Five9 makes I haven’t looked at their last quarterly earnings report, but I think they make more than that now and it turns out the market for if you took that software and made it cloud-based or a SaaS, it turns out the market is 10, maybe 25 times larger. And so I find the TAM is a tricky issue as an investor. What’s the minimum TAM number you want to see? Is it a billion? Is that the magic number?

Kevin:

Yeah, I, I, I will be very realistic here. I think both my experiences at FundersClub and Pear have taught me that, you know, at a minimum, you probably want to have at least a $2 billion TAM. I would even say that that’s perhaps even a little bit low. You know, you, you want to be a reasonable. So anywhere from like eight to 10 is probably a great number. If you’re talking like 50 north, you better have some good evidence to back that up. I’ve seen some founders list, like a 100 billion. It’s a little bit unreasonable because they haven’t properly sliced and diced it for their customer segment. And again, this is because you have to think about the incentive structure as a VC they’re raising these hundred million dollar funds. They have to return a minimum of 3X on that.

Kevin:

They’re looking for companies that can become unicorns. They never want to invest in a company where the growth is limited by the size of the market. And so if you’re not tackling a big, big market with a big vision and you don’t have the potential to become that unicorn, it’s hard for a VC to invest. So this doesn’t mean you should trick investors, but I think that you should try to do your very best to figure out, you know, if you’re under that $2 billion number, you should figure out well, am I thinking a little bit too small here? Is it because I’m only focused on this particular segment? Is there a way where I can present the data where perhaps this is my beach head market, but as I grow with a feature set, I can expand into this larger five to $10 billion market.

Kevin:

And as John mentioned, there are plenty of examples where TAMs may look small from the onset, whether that’s call centers, actually the founder of Shopify (NYSE: SHOP) recently, Toby, we recently released, I think he was like a, a large tweetstorm where he talked about how in the early days of raising for Shopify (NYSE: SHOP), you know, hundreds, like, I don’t know, I don’t think was hundreds, but maybe like dozens of investors turned them down because they said, well, how many individual creators are there? Are there on the internet who would actually want to start their own store? It seems like a small market and Toby at the time, even like, even, he couldn’t really answer that question, but what I think the entrepreneur or what the VCs failed to understand was that it was because of Shopify product. It was because there was no easy product online to help founders start an eCommerce store. That’s why the TAM was small. It was, it was like a self limiting issue because of, because there was no product and the moment they built a better product with a better experience, that’s when the TAM balloon like crazy. And that’s why Shopify is a public company now. So it is, yeah, it’s a business as a bit of a balance. Sometimes it’s hard to answer that question, but you have to be able to help an investor understand that fact because you know, better than they will.

John:

That reminds me of the time I got to chat briefly with Drew Houseton, the CEO of Dropbox oddly enough, at a Microsoft campus here in the Bay area. I don’t, we were both caught in Microsoft. And he was saying that all these VCs turned him down and the early days of Dropbox’s fundraising because they kept saying, why does the world need another Carbonite or GoToMyPC? And Drew’s response to them was, do you use Carbonite? So I find the TAM issue, or the TAM question is something that founders struggle with. The other one, I find some founders struggle with a lot is, and I hear this a lot. We have no direct competitors. How often do you find that that’s actually true that a startup has no direct competitors?

Kevin:

Not very true. And I think you should always be able to find some sort of direct competitor. It doesn’t even have to be, it could be adjacent. It could be like, this is an ironic example. Like Netflix says sleep as their competitor, like as a joke almost, but it’s typically actually a red flag, right? If a founder says we have no competitors a, it probably means that they haven’t done enough research and they’re just not self aware. And I think that’s an issue or B they’re a little bit too cocky about it. You, you, you want to show a little bit of humility and understanding like, Hey, maybe they’re not as specific a direct competitor, but they could be.

John:

Right. I was talking to a friend of mine, Steven Flowers, who’s a membership manager at the battery club here in downtown San Francisco. And he was saying, I rode my Peloton bike every day for four months. I was like, Jesus, Holy shit. Every day for four months. And he’s like me, we’re, you know, we’re not the most athletic people. And he said, well, the thing is, it’s a social network. Yeah. Like you can high five other people that are kind of, you know, doing the same routines as you, you have live instructors. And it made me realize Peloton is an existential threat to SoulCycle.

Kevin:

Right. They are, they very much.

John:

And so I find that when founders say, Oh, we have no direct competitors, they’re either lying or they haven’t thought it through total life. Okay. Now my favorite question, what are the not reflective of FundersClub or Pear or any of our friends, but in general, in a hypothetical or theoretical level, what are the top two lies that VCs tell founders when they want to invest?

Kevin:

This one? Actually a lot easier, so much easier to answer because man, I hear these a lot. So talk to you, lies VCs, tell founders. The first one is that they are interested in investing and typically through the investment or the diligence process, you will see a lot of VCs be like, Hey, look, I’m really interested. I want you to come, you know, go through this two week process with us and go through all this diligence we need, see your data room. The truth of the matter is, you know, VCs are not supposed to be investing in like 99% of the companies that they see. And I remember this even happened to us at Emmy when we went through the fundraising process recently this one VC, I’d been talking to the partner for several months. And then when I kicked off my fundraise, he said, come meet the rest of the partners.

Kevin:

Let’s do a partner meeting. We went there we did this whole meeting. They asked us all these really tactical questions. Well, it’s strange. They were like, Hey, so how did you do your demand testing? How did you build that community? And at the end of the meeting, they said, look, we really like you guys, you guys are the types of founders that we like to back. They use that specific language. And he said, but we really like you to come down to Sand Hill Road and do another partner meeting with us. I said, what the hell? Like I just did a partner meeting. So my cofounder and I went, we did that second partner meeting and that second partner meeting, they started grilling us again about all these tactical things about this business. They wanted to know how we came up with the idea. And then we slowly realized that they had actually never really invested in food and beverage at all.

Kevin:

And we were the first company they were really speaking to. And they were actually just milking us for information that they could transfer to their own portfolio companies. And I was a little bit peeved about this because a lot of VCs do information gathering. I think their job is to learn as much as they can about the market. And then, you know, pick the winner out of all of the different companies. So I think especially at the earliest ages, fundraising is an emotional game and most VCs, if they are interested, they will typically act very, very quickly. At least the best VCs typically do. I’ve seen some VCs literally give a term sheet within the next day. This is not necessarily the case for everyone. There’s obviously education as anywhere. But if you see that a VC is stringing you along, they’re taking several weeks.

Kevin:

They’re probably not excited. And that point, because fundraising is a game where you have to triage investors quickly and figure out who is excited about you, just move on, find another set of investors. Find people who are actually excited about your vision, excited about you as a team. So I think that’s the first thing. The second lie that VCs tell founders is that they are value add, this is no, this is, I think there’s a lot of VCs have claimed to be value add. You know, I think capital is probably specifically here in the US and, and here in SF Bay area, capital has really become a commodity. I think there’s something like 800 seed funds now, at least in 2019, from what I’ve heard. And so every VC has to stand out, right? It’s they all say something on their website.

Kevin:

Like we provide, we have this agency model, we have all these people that help you out. We help you with this. But truth of the matter is you know, you are just one company within their portfolio. VCs are spread pretty thin to begin with. There are some VCs who will help out, but you know what I usually tell founders, like, look even though it has become a more founder centric market at the end of the day, you kinda have to remember that VC as an asset class was created because they were investing in this asset class that no one else wanted to touch. It was so risky. And we kind of forget that VCs are here to invest in us because no one else will and we should just go execute and we should just go build ourselves. And if you, as a founder are constantly relying on your VC for value add, there’s probably an issue where you as a founding team, like if you can’t help yourselves first, I don’t know where you’re going to go as a startup. And so you know, that’s not to say certain VCs are not value add, but try not to read too much into it, right? Like you should obviously appreciate that. They took a chance on you. There are some partners who are gonna be extremely valuable who are former founders or operators. But the majority of the time don’t rely on them to be the value add to grow your company. That’s on you.

John:

One that I hear often a few years ago my friend Matthew Kimball was kind enough to invite me to Matt Danzeisen and his husband, Peter Thiel new year’s Eve party. They have this spectacular new year’s Eve party of their house in the Hollywood Hills. And so, you know, for a couple hours, I got to rub elbows with Richard Davis and there was a VC that I knew and I won’t say his name, but you know, we said hi to each other. And I said, you know, I read a recent blog post on your, your guys’ corporate blog about how your founder friendly. And I, and I think that’s such a great thing. And he said, Oh, John, that’s just marketing. He said, wait, is that Bryan Singer over there? Let’s go talk to him. You know? And I thought, wow, this is why I’m not an investor. I know nothing about this world. And I hear that a lot, like, Oh, we’re founder friendly, but what I’ve come to learn at the end of the day is look you know, like we’ve been at Y Combinator demo days, right? Where we say hi to a high powered VC that works at a tier one fund. And then suddenly one of their LPs walks by they freak. And they’re like, Oh my God.

John:

And you realize like, look, shit always rolls downhill. Right. There’s always someone pushing a ball of shit down on you. And at the end of the day, VCs are beholden to their LPs to provide a return. Right, right. They’re not looking to help you become a multimillionaire or change the world or fulfill your destiny as a CEO or CTO. They got to take care of themselves and their families, a lot of these are family, family, guys, and family gals. And so I think the whole like, Oh, we’re founder friendly to me, it’s kind of like the whole like, Oh, we’re value add. Right. Or that cliche, like, how can I be helpful?

John:

And usually you tell them, you know, your investors, like we need to hire three developers. Like it’s really hard, you know, with the money we raised in SF. And they’re like, great. Let me introduce you to my friend who runs a recruiting agency when they charge 47% of annual salary. Okay. Last question. I’ll let you go. What do you think is since we’re both in San Francisco right now are we at peak San Francisco? I mean, we’re dealing with so many issues and rising costs. And I see at least at JetBridge, the company I’m running right now, we see tons of great developers in Ukraine and Poland. I hear rumblings about Vietnamese developer communities there like being really good. South America is growing. What’s the future of San Francisco in terms of its continued dominance or as the continued headquarters of tech innovation.

Kevin:

Yeah, this is, this is a great question. You know, going back to, so I still believe that San Francisco is, you know, the scene or what I talked about earlier. It was an environment you do want to be a part of, at least for a while because the network and connections you build here, they will carry for the rest of your life. Now, as John mentioned, I think a lot of people are starting to recognize that San Francisco extremely expensive. I mean, it always really has been, but even more so now real estate rent for office, it’s just, it’s so ridiculous. It doesn’t even make sense from a burn perspective.

John:

Honestly for the folks that have not spent a good amount of time in San Francisco, it’s become ridiculous. It’s crazy. My wife and I just spent a week in New York city and going out in New York city used to be the most expensive, ridiculous place. But when we would go out, you know, having lunch or dinner in New York city, it’s a good 20% cheaper than San Francisco. London is cheaper than San Francisco. Are we at peak San Francisco?

Kevin:

It’s so hard to say because, you know, I’ve talked to some people who’ve, who’ve also, you know, they a few of my friends continue to invest in real estate in San Francisco and they say, we’re only gonna go up from here because this concentration of wealth and talent, and really it’s all about the talent, right? It’s where the talent flow goes is really where the next Mecca goes. And there’s a lot of rumblings in San Francisco. A lot of people are dwelling a lot on future of work now, especially around remote work. And, you know, we’ve seen a lot of really hot companies. Tandem was a recent one in the recent YC batch that got a lot of attention. I think they raised from Andreessen to, to focus on remote work collaboration, I think because we’re, I think because of tools like that you’re going to start to see this, like this colocalization that acquirement of being local not be as important as it used to be.

Kevin:

And there are smart people all around the world. I think, you know, a big motto of mine has always been that, you know, talent is universal. Opportunity is not, I still believe that to this day. I think where the scene is important still in San Francisco is just because it’s just, it’s, it’s kind of gone to a critical mass at this point where, you know, you still want to be around these people because that’s where you’ll learn the fastest it’s you want the repeat interactions? You want the ability to just walk down the street, bump into a developer, an investor, a founder. But I think over time, I can’t imagine it’s going to last that’s, that’s a personal belief of mine. I think that we’re already seeing very prominent, huge companies around the world companies like GitLab who, you know, are running fully remote with no issue whatsoever. And so I think this is, you know, remote work is only going to accelerate going forward. I think San Francisco will still continue to be, you know, a minor superpower, just like how LA has always been kind of like Hollywood media, New York finance, and, you know, increasingly some more consumer brands out there. But you know, you’ll have these kind of these headquartered areas and then everything else will be remote so

John:

Well to your point, you mentioned Gitlab fully distributed team yet a few months ago, Forbes held a party for some of its writers at a wood working workshop. And I made a bottle opener, a beer bottle opener with Sid the CEO of GitLab again only in San Francisco. Right? Yeah. Kevin, thank you so much. Best of luck with Emmy and hope we can

Kevin:

Appreciate it. Thanks brother. Take care. Thanks.

Python 2020: Modern Best Practices

Python and related tooling continues to progress and evolve. I’d like to share some of the tools and practices we’re using at JetBridge to develop python web applications.

This is by no means an exhaustive account or a definite list of all best practices, and I hope readers will share what’s working well for them so I can learn and incorporate that knowledge. I don’t know about everything out there but I can at least present a survey of what we’ve been using on multiple projects with success.

Python

Let’s start with… python. As of January 1st, 2020 python 2 support was officially discontinued. If you are still maintaining any python 2 code you are using the language equivalent of Windows XP. Not only is python 2 no longer receiving security updates but now all python module authors will feel comfortable dropping any support for python 2 in any future versions of their modules, which means your dependencies are unlikely to receive security updates as well. Using python 2 is now a legitimate security risk.

Python 3.8 is out. What’s new in it?

The “walrus operator” := allows you to initialize a variable as part of any expression and save a line or two of code. The battle in PEP 572 over getting this operator included in the language was so unpleasant that it caused Guido van Rossum to ragequit his Benevolent Dictator For Life of Python role.

__pycache__ directories are now managed out-of-tree so they stop polluting your deployments and source control.

New additions to python’s type system – TypedDict lets you define the shape of a dictionary type, Literal lets you easily construct literal value constraints such as for enumerated value options, and at long last we have built-in support for structural subtyping, also known as Protocols.

F-string debug syntax – now instead of writing:

print(f"blorp={blorp}")

You can write:

print(f"{blorp=}")

Which is terrific news for those of us who will continue using print statements to debug until the day we die.

Python 3.9 is expected out in October 2020.

Linting and Formatting

Keeping your code neat and formatted can really help with readability and enforcing a consistent style. The tooling can also help catch potential bugs or mistakes. Here’s what we’re using:

Flake8 – Classic Linting Tool

Run as a pre-commit hook or in your CI flow. We suggest installing and enabling the plugins:

tox.ini configuration:

[flake8]

ignore = E305,E402,E501,I101,I100,I201

max-line-length = 160

exclude = .git,__pycache__,build,dist,.serverless,node_modules,migrations,.venv,.bento

enable-extensions = pep8-naming,flake8-debugger,flake8-docstringsMypy – Type Checking

Mypy performs the useful function of type-checking, to the extent one can in python. It does on some occasions catch useful errors for you and is improving as time goes on. Still, the usefulness of python’s bolted-on type system afterthought is limited compared to say, any other typed language.

If you are adding it to an existing project with many dependencies you may need to add ignore_missing_imports = True to your mypy.ini configuration file until you can resolve all of the warnings you’re going to get.

Bento – Static Analysis

Bento is a very new tool that attempts to be sort of a meta-linter, combining a number of different checker tools into one, most notably Bandit, a “Security oriented static analyser for python code.” It’s designed to integrate into git hooks and CI workflows relatively easily. It’s still quite new and not super mature yet but this is definitely a tool to keep your eye on. The analysis engines are open source and provided for free, though the company behind it is working to offer paid features for larger teams.

Black – Formatting

Black is a brutal and fantastic code formatter, much like prettier for python. It can be run as a pre-commit hook to make sure your code is formatted correctly, or you can have your editor run it automatically on save (my preference). It is technically possible to modify the formatting rules but there is no reason you should ever do that. Just enable it, always run it on every changed file, and never worry about 97% of code formatting issues ever again.

Workflow Integration

People are of differing opinions on whether you should add these tools into your editor, git hooks, or CI pipeline. Personally I have all of these tools hooked into my editor (mostly spacemacs but giving PyCharm a try) and love having my code formatted upon saving and seeing type errors inline in my code. This is definitely the best way to develop but it doesn’t enforce any standards in your team. Maybe you can always expect the people working on your project to have their editors configured correctly but this is mostly unrealistic for most teams.

You can add it as a pre-commit (or pre-push) git hook, which ensures everything is run before it goes to CI. The downside is this can add extra setup steps for the project or greatly increased execution time for common git commands.

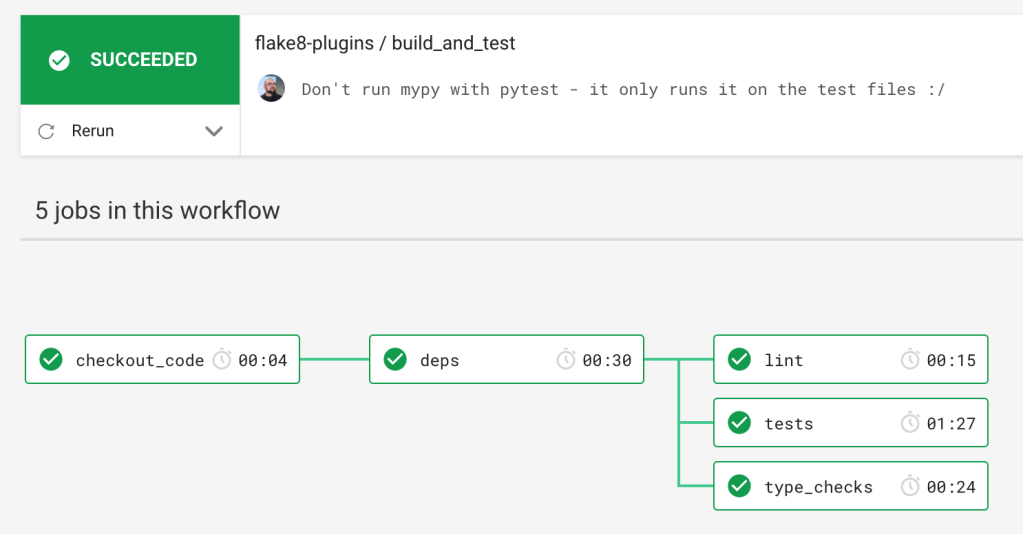

Another option is to run all of your checks in CI and let developers be responsible for committing code that is correct or suffer failed tests. I have CircleCI configured to install dependencies and then run the checks as separate jobs in parallel.

And these options are not mutually exclusive. You can totally do all three together.

Testing

Switching away from unittest.TestCase and lots of custom helper functions to create objects in favor of pytest fixtures and factoryboy made testing vastly more pleasant, especially when writing tests that talk to the database.

Our setup for writing tests that interact with Flask and SQLAlchemy is to set up fixtures with factoryboy which helps you declaratively write fixture factories for all your database models and pytest-factoryboy which lets you register your factories as pytest fixtures. The plugin pytest-postgresql allows easy creation of a PostgreSQL database for running tests and pytest-flask-sqlalchemy patches in a mocked database session (or sessionmaker or engine if you need them) during tests that ensures each test runs in a subtransaction. Subtransactions (aka SAVEPOINT) allow you to run each test isolated in its own transaction and all changes are rolled back at the end of the test. This allows each test to be invisible to any other test or transaction and also to have all database changes cleaned up automatically. This is the most efficient way to run database tests with a high degree of reproducibility to how your application will be running for real.

There are a lot of pieces here but they fit together beautifully in the end. Your test setup may look something like this:

myapp/db/fixture.py – where we like to define database factories. These can be used for populating development environments and tests with sample DB rows.

from faker import Factory as FakerFactory

import factory

from jetkit.db import Session # see https://github.com/jetbridge/jetkit-flask/blob/e3fc3448933ffbfb573cc1dfc873364cd17d4aca/jetkit/db/__init__.py#L10

faker: FakerFactory = FakerFactory.create()

class SQLAFactory(factory.alchemy.SQLAlchemyModelFactory):

"""Use a scoped session when creating factory models."""

class Meta:

abstract = True

# by providing access to our current sqlalchemy session the factory can automatically

# add newly-created objects to the session (i.e. insert into the DB)

sqlalchemy_session = Session

class UserFactoryFactory(SQLAFactory):

"""Base class for user factories with common fields."""

class Meta:

abstract = True

dob = factory.LazyAttribute(lambda x: faker.simple_profile()["birthdate"])

name = factory.LazyAttribute(lambda x: faker.name())

password = 'my-default-pw!'

avatar_url = factory.LazyAttribute(

lambda x: f"https://placem.at/people?w=200&txt=0&random={random.randint(1, 100000)}"

)

class NormalUserFactory(UserFactoryFactory):

"""Create a user with type=Normal."""

class Meta:

model = NormalUser

email = factory.Sequence(lambda n: f"normaluser.{n}@example.com")

This sets us up with a factory that can produce NormalUser objects. In our setup we use SQLAlchemy polymorphism to distinguish between different user types with different model classes and the UserFactoryFactory (how very enterprise) gives us a base class to quickly define factories for each type of user model.

myapp/test/conftest.py – place to add fixtures made available to your tests. Documentation on these fixtures is provided here.

from myapp.db.fixtures import NormalUserFactory

from pytest_factoryboy import register

register(NormalUserFactory)

This register helper function takes our factory and creates two pytest fixtures out of it. One fixture will be called normal_user which will always return a user object in our DB session, created on demand once per test. The other fixture will be normal_user_factory which will accept arguments to override the factory defaults.

Next we set up fixtures for database, app, and our DB session:

@pytest.fixture(scope="session")

def database(request):

"""Create a Postgres database for the tests, and drop it when the tests are done."""

with DatabaseJanitor(DB_USER, DB_HOST, DB_PORT, DB_NAME, DB_VERSION):

yield

This provides a new database for the entire test session – it’s only created once and dropped when everything is finished.

@pytest.fixture(scope="session")

def app(database):

"""Create a Flask app context for tests."""

# here we pass in config overrides to our create_app

app = create_app(config=dict(SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI=DB_CONN, TESTING=True))

with app.app_context():

yield app

The above code provides us with a Flask app and context for the duration of the entire test session. You can push a new context for each test if you like (remove the scope fixture argument) but I’ve never needed to do this.

@pytest.fixture(scope="session")

def _db(app):

"""Provide the transactional fixtures with access to the database via a Flask-SQLAlchemy database connection."""

from myapp.db import db

db.create_all()

return db

This is the magic hook to provide our database session to pytest-flask-sqlalchemy. We need to provide the package of our SQLAlchemy instance to our pytest configuration in tox.ini:

[pytest]

# mock sqlalchemy database session during testing

mocked-sessions = myapp.db.db.session

Now we can define a fixture for a HTTP client to talk to our app:

@pytest.fixture

def client(app, normal_user):

# get flask test client

client = app.test_client()

access_token = create_access_token(identity=normal_user)

# set environ http header to authenticate user

client.environ_base["HTTP_AUTHORIZATION"] = f"Bearer {access_token}"

return client

This fixture has a dependency on two other fixtures; app and normal_user. We defined the app fixture just above, and the normal_user fixture is automatically added for us by the pytest_factoryboy register helper.

So now that we have a client fixture and a normal_user fixture, we can write very straightforward tests for API calls. Suppose we want to test a user API:

def test_user_api(client, normal_user):

response = client.get("/api/user/0")

assert response.status_code == 404

user_response = client.get(f"/api/user/{normal_user.id}")

assert user_response.status_code == 200

assert user_response.json.get("id") == normal_user.id

The simplicity and compactness of this test is striking. We don’t have any test cases, we define our dependencies in the function arguments, we use straightforward assert statements to check our responses. The test runs in an isolated subtransaction, dependency injection is performed to load the complete dependencies for this particular test, and it couldn’t possibly be any cleaner.

If you’re curious why we’re doing a simple assert here and not something like self.assertEqual() the answer is that pytest overrides the built in assert function with a more test-friendly and powerful version. You will still receive output exactly as you would expect from any test framework if the assertion fails. See the pytest documentation for more details.

Virtual Environments ﹠ Dependencies

The most modern tool for managing dependencies and virtual environments is Pipenv. It’s a bit more npm-style than venv or virtualenvwrapper, with a lockfile, split dev dependencies, and environment management via command line instead of sourcing anything in your shell. It saves the virtual environment files away out of tree.

The downsides for Pipenv are that it is frankly super slow and there hasn’t been an official release in over a year despite very active development. I hope that a faster new release will come out sometime soon.

Pipfiles are the future, no reason to be using requirements.txt anymore.

One more feature that may be of interest to some is the ability to define multiple sources in a Pipfile. If you have certain dependencies that need to be pulled from an internal package index server for example, you can define that source for only those dependencies instead of having to globally change your pypi mirror.

Web Framework

Some of the popular modern web frameworks are Django, Flask, and Falcon.

Django

Django is a pretty heavy solution but has the benefit of everything being set up for you. It’s not a tool I reach for because I normally only try to create lightweight API servers, with little to no server-side rendering of HTML, and I don’t find Django as suited to a serverless architecture as something more lightweight.

Flask

Flask has been our go-to tool for years. It gives you a basic core into which you can plug in components and features as needed. The setup involved in creating the perfect enterprise-ready Flask app from scratch is considerable and takes some experience to get right on your own. The flexibility and ability to craft an application perfectly suited to your needs is invaluable for serious projects, and the simplicity and whipupitude makes it perfect for dead-simple services too.

I’ve written at length about writing serverless web applications with Flask:

- https://spiegelmock.com/2018/11/21/rapid-api-serverless-development/

- https://spiegelmock.com/2018/09/06/serverless-python-web-applications-with-aws-lambda-and-flask/

Falcon

If Flask is too heavy for you, there’s the Falcon microframework. If you’re writing a web service for a system with 64k of RAM and it’s not talking to any database or external services and the CPU overhead of handling HTTP requests and responses is the main bottleneck, Falcon may be a good choice. Their documentation really emphasizes how fast it is. I don’t think your web framework is usually the primary concern when it comes to speed but doubtless there are situations where this is needed.

Digression: Request Globals

<Digression>

There is one funky aspect of how Flask provides access to the current “app” context and the current request context that bothers or confuses some people. There exists an instance of your web application that contains configuration, routes, error handlers, and extensions that comprise your app. When your app is started up a new “app context” is pushed onto the app context stack to keep track of what app is currently active:

from myapp import app

with app.app_context():

do_stuff_with_my_app()

In any code running inside of this context, you can access the current application.

from flask import current_app

def do_stuff_with_my_app():

print(current_app.config['SOME_KEY'])

What’s important here is that current_app is a context variable proxy, which you can treat like a global variable but actually belongs to a context stack and is thread safe. Typically you only need to deal directly with pushing an app context if you’re writing scripts or wrappers that utilize your Flask app instance.

A similar approach is used for the current request context. When your Flask app is running (inside an app context) and a new request comes in, a new request context is pushed onto the request context stack to keep track of the request and request-local variables.

So whereas in many web frameworks like node’s Express you get passed in request and response objects as part of your handler:

app.post('/', function(request, response) {

console.log(request.body);

response.send(request.body);

})

Or in python’s Falcon:

import json

import falcon

class Resource(object):

def on_post(self, req, resp):

body = json.load(req.stream)

print(body)

resp.body = body

resp.status = falcon.HTTP_200

In Flask one might write:

from flask import request

@app.route("/", methods=["POST"])

def app_index():

body = request.get_json()

print(body)

return body